Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination on 30 January 1948 shook the nation. Even today, his teachings of peace and harmony continue to inspire millions. As we observe his Punyatithi in 2025, take a moment to understand the events of that day and why his sacrifice is remembered every year on Martyrs’ Day.

Mahatma Gandhi, fondly known as the Father of the Nation, was assassinated on 30 January 1948 in New Delhi. His death was a moment of deep sorrow for India and the world. Gandhi was a pioneer of non-violent resistance and played a crucial role in India’s freedom struggle against British rule. His efforts led to India’s independence on 15 August 1947.

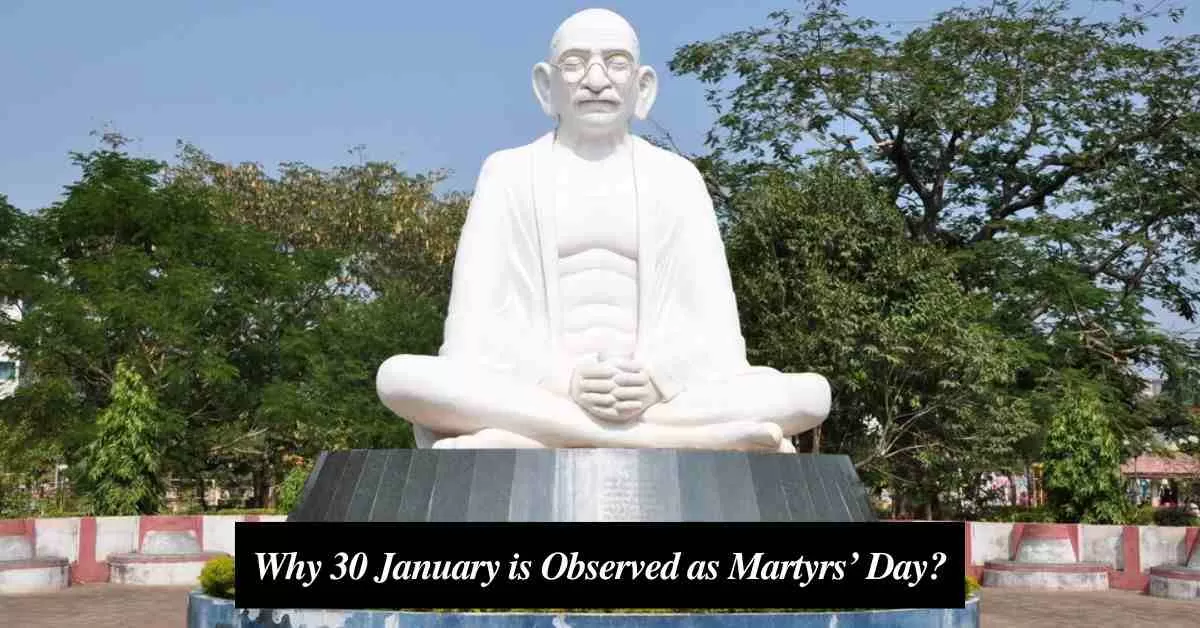

To honor his sacrifice, 30 January is observed as Martyrs’ Day (Shaheed Diwas) across India. On this day, people pay tribute to him and remember his ideals of truth (Satya) and non-violence (Ahimsa), which became the foundation of his fight for justice. Schools, colleges, and various institutions organize events to educate people about his teachings.

What Happened on 30 January 1948?

On 30 January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was in New Delhi, staying at Birla House (now known as Gandhi Smriti). As usual, he was preparing for his evening prayer meeting. Many people had gathered to listen to his prayers and teachings.

At around 5:17 PM, Gandhi walked towards the prayer ground. He was weak due to fasting and was supported by his grandnieces, Abha and Manu. Suddenly, a man named Nathuram Godse stepped forward from the crowd.

Without warning, Godse pulled out a pistol and fired four bullets at Mahatma Gandhi from close range. Gandhi fell to the ground and, according to reports, his last words were “Hey Ram”, expressing his faith in God.

People around were shocked and rushed toward him. He was carried inside Birla House, but the wounds were too serious. Within a few minutes, Mahatma Gandhi passed away.

Who Was Nathuram Godse?

Nathuram Godse was a Hindu nationalist who was against Gandhi’s policies. He blamed Gandhi for favouring Muslims during the Partition of India and believed that Gandhi’s decisions had weakened India.

Godse and his accomplice Narayan Apte were arrested immediately. After a trial, Godse was sentenced to death and was executed on 15 November 1949.

Why Is 30 January Observed as Martyrs’ Day?

Since 1948, 30 January has been observed as Martyrs’ Day to honour Gandhi and other martyrs who sacrificed their lives for India. On this day:

The President, Prime Minister, and other leaders pay tribute to Gandhi at Raj Ghat (his memorial in Delhi).

A two-minute silence is observed across the country at 11:00 AM to remember Gandhi.

Schools and institutions organize events to teach students about Gandhi’s life and principles.

Mahatma Gandhi’s Legacy

Even after his death, Gandhi’s message of truth, non-violence, and peace continues to inspire people around the world. His teachings played a major role in many global movements for civil rights and freedom.

In conclusion, his principles are still relevant today, reminding us of the power of love, unity, and non-violence. As India observes Mahatma Gandhi Punyatithi in 2025, it is a time to reflect on his sacrifices and follow his path of peace and harmony.

Mahatma Gandhi (born October 2, 1869, Porbandar, India—died January 30, 1948, Delhi) was an INDIAN lawyer, politician, social activist, and writer who became the leader of the INDIAN INDEPENDENCE

MOVEMENT against BRITISH RULE. As such, he came to be considered the father of his COUNTRY. GANDHI is internationally esteemed for his DOCTRINE of nonviolent protest (satyagraha) to achieve political and social progress.

In the eyes of millions of his fellow Indians, Gandhi was the Mahatma (“Great Soul”). The unthinking adoration of the huge crowds that gathered to see him all along the route of his tours made them a severe ordeal; he could hardly work during the day or rest at night. “The woes of the Mahatmas,” he wrote, “are known only to the Mahatmas.” His fame spread worldwide during his lifetime and only increased after his death. The name Mahatma Gandhi is now one of the most universally recognized on earth.

Youth

Gandhi was the youngest child of his father’s fourth wife. His father—Karamchand Gandhi, who was the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar, the capital of a small principality in western India (in what is now Gujarat state) under British suzerainty—did not have much in the way of a formal education. He was, however, an able administrator who knew how to steer his way between the capricious princes, their long-suffering subjects, and the headstrong British political officers in power.

Gandhi’s mother, Putlibai, was completely absorbed in religion, did not care much for finery or jewelry, divided her time between her home and the temple, fasted frequently, and wore herself out in days and nights of nursing whenever there was sickness in the family. Mohandas grew up in a home steeped in Vaishnavism—worship of the Hindu god Vishnu—with a strong tinge of Jainism, a morally rigorous Indian religion whose chief tenets are nonviolence and the belief that everything in the universe is eternal. Thus, he took for granted ahimsa (noninjury to all living beings), vegetarianism, fasting for self-purification, and mutual tolerance between adherents of various creeds and sects.

The educational facilities at Porbandar were rudimentary; in the primary school that Mohandas attended, the children wrote the alphabet in the dust with their fingers. Luckily for him, his father became dewan of Rajkot, another princely state. Though Mohandas occasionally won prizes and scholarships at the local schools, his record was on the whole mediocre. One of the terminal reports rated him as “good at English, fair in Arithmetic and weak in Geography; conduct very good, bad handwriting.” He was married at the age of 13 and thus lost a year at school. A diffident child, he shone neither in the classroom nor on the playing field. He loved to go out on long solitary walks when he was not nursing his by then ailing father (who died soon thereafter) or helping his mother with her household chores.

He had learned, in his words, “to carry out the orders of the elders, not to scan them.” With such extreme passivity, it is not surprising that he should have gone through a phase of adolescent rebellion, marked by secret atheism, petty thefts, furtive smoking, and—most shocking of all for a boy born in a Vaishnava family—meat eating. His adolescence was probably no stormier than that of most children of his age and class. What was extraordinary was the way his youthful transgressions ended.

“Never again” was his promise to himself after each escapade. And he kept his promise. Beneath an unprepossessing exterior, he concealed a burning passion for self-improvement that led him to take even the heroes of Hindu mythology, such as Prahlada and Harishcandra—legendary embodiments of truthfulness and sacrifice—as living models.

In 1887 Mohandas scraped through the matriculation examination of the University of Bombay (now University of Mumbai) and joined Samaldas College in Bhavnagar (Bhaunagar). As he had to suddenly switch from his native language—Gujarati—to English, he found it rather difficult to follow the lectures.

Meanwhile, his family was debating his future. Left to himself, he would have liked to have been a doctor. But, besides the Vaishnava prejudice against vivisection, it was clear that, if he was to keep up the family tradition of holding high office in one of the states in Gujarat, he would have to qualify as a barrister. That meant a visit to England, and Mohandas, who was not too happy at Samaldas College, jumped at the proposal. His youthful imagination conceived England as “a land of philosophers and poets, the very centre of civilization.” But there were several hurdles to be crossed before the visit to England could be realized. His father had left the family little property; moreover, his mother was reluctant to expose her youngest child to unknown temptations and dangers in a distant land. But Mohandas was determined to visit England. One of his brothers raised the necessary money, and his mother’s doubts were allayed when he took a vow that, while away from home, he would not touch wine, women, or meat. Mohandas disregarded the last obstacle—the decree of the leaders of the Modh Bania subcaste (Vaishya caste), to which the Gandhis belonged, who forbade his trip to England as a violation of the Hindu religion—and sailed in September 1888. Ten days after his arrival, he joined the Inner Temple, one of the four London law colleges (The Temple).

Sojourn in England and return to India of Mahatma Gandhi

Gandhi took his studies seriously and tried to brush up on his English and Latin by taking the University of London matriculation examination. But, during the three years he spent in England, his main preoccupation was with personal and moral issues rather than with academic ambitions. The transition from the half-rural atmosphere of Rajkot to the cosmopolitan life of London was not easy for him. As he struggled painfully to adapt himself to Western food, dress, and etiquette, he felt awkward. His vegetarianism became a continual source of embarrassment to him; his friends warned him that it would wreck his studies as well as his health. Fortunately for him he came across a vegetarian restaurant as well as a book providing a reasoned defense of vegetarianism, which henceforth became a matter of conviction for him, not merely a legacy of his Vaishnava background. The missionary zeal he developed for vegetarianism helped to draw the pitifully shy youth out of his shell and gave him a new poise. He became a member of the executive committee of the London Vegetarian Society, attending its conferences and contributing articles to its journal.

In the boardinghouses and vegetarian restaurants of England, Gandhi met not only food faddists but some earnest men and women to whom he owed his introduction to the Bible and, more important, the Bhagavadgita, which he read for the first time in its English translation by Sir Edwin Arnold. The Bhagavadgita (commonly known as the Gita) is part of the great epic the Mahabharata and, in the form of a philosophical poem, is the most-popular expression of Hinduism. The English vegetarians were a motley crowd. They included socialists and humanitarians such as Edward Carpenter, “the British Thoreau”; Fabians such as George Bernard Shaw; and Theosophists such as Annie Besant. Most of them were idealists; quite a few were rebels who rejected the prevailing values of the late-Victorian establishment, denounced the evils of the capitalist and industrial society, preached the cult of the simple life, and stressed the superiority of moral over material values and of cooperation over conflict. Those ideas were to contribute substantially to the shaping of Gandhi’s personality and, eventually, to his politics.

Painful surprises were in store for Gandhi when he returned to India in July 1891. His mother had died in his absence, and he discovered to his dismay that the barrister’s degree was not a guarantee of a lucrative career. The legal profession was already beginning to be overcrowded, and Gandhi was much too diffident to elbow his way into it. In the very first brief he argued in a court in Bombay (now Mumbai), he cut a sorry figure. Turned down even for the part-time job of a teacher in a Bombay high school, he returned to Rajkot to make a modest living by drafting petitions for litigants. Even that employment was closed to him when he incurred the displeasure of a local British officer. It was, therefore, with some relief that in 1893 he accepted the none-too-attractive offer of a year’s contract from an Indian firm in Natal, South Africa.